Seven Questions with Buey Ray Tut

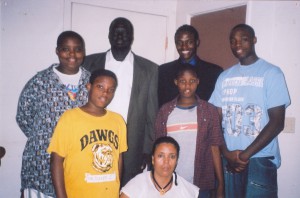

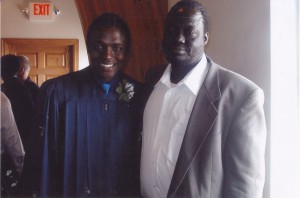

He moved from Maiwut, South Sudan to Tennessee, then to Minnesota, and finally to Omaha, Nebraska with his family at age 11. Ten years later he was a member of the Omaha Public Library Board, student body vice president at UNO, district executive for the Boy Scouts, and co-founder of Aqua-Africa, Inc.

Find out what makes Buey tick.

What is your fondest childhood memory growing up in South Sudan?

One thing that is distinctly memorable is that whenever we would have big windstorms, the mango trees would shake and the fruit would fall. Your mom would get upset that you would run outside. So when she turned her back you would just bolt outside, you don’t even ask for permission, and then you’d grab a bunch of mangoes and run back into the hut. It was very dangerous, since branches and things could fall down on you. But then you had mangoes. So it was way worth the risk! I think my mother would even agree with that right now.

One thing that is distinctly memorable is that whenever we would have big windstorms, the mango trees would shake and the fruit would fall. Your mom would get upset that you would run outside. So when she turned her back you would just bolt outside, you don’t even ask for permission, and then you’d grab a bunch of mangoes and run back into the hut. It was very dangerous, since branches and things could fall down on you. But then you had mangoes. So it was way worth the risk! I think my mother would even agree with that right now.

How did you get involved with the co-founders of Aqua-Africa?

Jacob Khol and I have known each other since childhood. We’re from the same area, but two different villages in South Sudan. When we first discussed how we wanted to go back there and what we wanted to do, the first thing we thought about was the one thing we wished we had growing up, which was access to clean water. Jacob is a very relatable guy. He’s very analytical when it comes to understanding cultures and how they function, so he was instrumental, initially, in deciding that we shouldn’t just go back to our village first, we should go to a different part of the country, to break up that tribal kind of mentality.

I also knew Buay [Wiyual] briefly from South Sudan and we met again here in the US. What I really like about Buay was when we first shared our vision with him, he completely bought into it. He said, “That’s exactly what I want to do too, to provide that kind of service in South Sudan, but away from our village.” So it was really cool to find two other guys who saw the problem and said, ok, let’s do this.

Jacob is good at analyzing what would be feasible and culturally appropriate. Buay — on the operations side — has a construction background, so he understood how it all needed to be done. For him, working with the people directly is the most important aspect.

What made you want to devote your energy to drilling wells in South Sudan in the first place?

In college, Jacob and I were talking about what we could do to help South Sudan. The country was just emerging from war. We thought about what we missed when we were kids. We remembered that whenever we would leave the house, our moms would see us walking around and make us go get water with her. And we hated that job! It was too far, too long. And you missed soccer, most importantly. But then we realized how it affected our moms. We were being selfish at the time, but she was the one who cooked, cleaned, and tended to the farm. We realized how lucky we were to not be girls. They were expected to get water all the time. They were missing school and things like that. So we decided we wanted to go provide access to water.

Tell us about your travels to and from Africa.

I stay with my family when I’m in Juba [County, South Sudan]. I never stay in a hotel; it’s too expensive. I eat with the villagers, and sometimes it’s terrible food. Rice and beans is what they offer every day! One time they said they were going to sacrifice a goat, which I am usually against. But after rice and beans for a month, I was thinking, let’s go!

adobe photoshop cs6 trial download

On a more serious note, just being from South Sudan, and then being from the United States, I’ve learned that challenge is not unique to Africa. But we have unique challenges in Africa. The only way we can get out of those unique challenges is by unique solutions, carried out by the people there. So they have to want it. I feel like I’m in two different worlds. The first time I ever felt like this country was my own was when I went to drill in South Sudan in 2011. As I was coming back the US border agent looked at my passport and my visa, and I told him I had been in South Sudan drilling wells for the last few months. And he was like, “That’s great! Welcome home.” That made me realize I truly am an American here. And I appreciate everything this country has done for me. But going back, it gives you a perspective from two different worlds. And usually, that’s when change happens, when traders go to a different country and come back.

On a more serious note, just being from South Sudan, and then being from the United States, I’ve learned that challenge is not unique to Africa. But we have unique challenges in Africa. The only way we can get out of those unique challenges is by unique solutions, carried out by the people there. So they have to want it. I feel like I’m in two different worlds. The first time I ever felt like this country was my own was when I went to drill in South Sudan in 2011. As I was coming back the US border agent looked at my passport and my visa, and I told him I had been in South Sudan drilling wells for the last few months. And he was like, “That’s great! Welcome home.” That made me realize I truly am an American here. And I appreciate everything this country has done for me. But going back, it gives you a perspective from two different worlds. And usually, that’s when change happens, when traders go to a different country and come back.

What do your parents think of your work with Aqua-Africa?

With my father’s political career [former war coordinator for Sudan People’s Liberation Army], he’s actually afraid about me going back to South Sudan, because to him it sounds a bit dangerous, because he knows what could go wrong. But at the same time he does everything he can to help out, whether it’s communicating with villagers, calling over there, just continuously paying attention to what’s taking place, and discerning what’s really relevant.

With my father’s political career [former war coordinator for Sudan People’s Liberation Army], he’s actually afraid about me going back to South Sudan, because to him it sounds a bit dangerous, because he knows what could go wrong. But at the same time he does everything he can to help out, whether it’s communicating with villagers, calling over there, just continuously paying attention to what’s taking place, and discerning what’s really relevant.

Although he’s reluctant, he does take a big advisory role in Aqua-Africa. He goes above and beyond with getting us information. Whenever he hears snippets of what’s going on in South Sudan, he makes sure he relays it to us. And whenever I’m in South Sudan, he’s on complete alert.

So, what makes you laugh?

[Pauses.] Well, I enjoy a lot of books. I volunteer for Boy Scouts. We have an all-Sudanese troop. I’m an assistant Scoutmaster. I love what I do there. I run a lot! That helps relieve stress. I do like some TV shows. Battlestar Galactica. I guess a lot of people don’t know this about me, but I do love Sci-Fi. In an unhealthy amount. No one knows that about my older brother either – he has a bunch of theories about UFOs. That’s one thing that keeps us close, that we both love Sci-Fi. I have seen every episode of Star Trek and I quote them like crazy.

Whoa! The secret is out now. Is there anything else you’d like people to know about you?

My ex-girlfriend used to say we’re a bit too idealistic about what’s going on in Africa. But having said that, I think we’re what’s next for Africa. We’re what can take it to another level. And the good thing is, America and the rest of the world are willing to help. We’re fortunate to be here. I consider America home. But I feel privileged to have enough education to be able to go back to South Sudan, too. And it would be a travesty if we didn’t apply what we learn here and use it to advance South Sudan and Africa. I know that’s a lofty goal, but we’re taking it on.